As Americans prepare to go to the polls or mailboxes to elect the next president, many are focused on the policies or personalities of Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. But there’s a larger issue looming—one that goes beyond any single election cycle: has the presidency become too powerful? This concern goes back to America’s founding, as some leaders were understandably wary of vesting too much power in a single individual after having just cast off the shackles of the oppressive British monarchy. During the debate over ratifying the Constitution, Founding Father and Governor of Virginia Edmund Randolph ominously warned that the executive branch as outlined in Article II was a “foetus of monarchy”, capable of growing and evolving into a king-like authority.

(I will henceforth spell the term “fetus”, because we defeated Britain so we get to spell it our way now.)

Randolph wasn’t the only one concerned with the Constitution’s guardrails against authoritarianism: Patrick Henry, prominent Founding Father and coiner of the term “Give me liberty or give me death”, stated that “your president may easily become king.”

It’s been 235 years since the Constitution was ratified over the concerns of Randolph, Henry, and the Anti-Federalists, and things are going… not great? The growth of executive power since the War on Terror has been difficult to ignore. So I thought it would be a great time to check in on how the “fetus of monarchy” has grown over time—has executive power evolved beyond the founders’ intentions? Or are we simply seeing the presidency adapt to the needs of an increasingly complex modern America? This is the first in a series of articles following the expansion of executive authority from the ratification of the Constitution through today.

The Fetus is Conceived: Let’s Talk About Article II

Article II of the United States Constitution outlines the presidency:

The president must faithfully execute the laws passed by Congress.

The president will serve as the commander-in-chief of any armed forces.

The president can appoint judges, ambassadors, and other high-ranking officials, including “officers of the United States.”

The president can receive ambassadors from other countries and is responsible for negotiating treaties.

The president can pardon people for federal offenses.

That’s basically it for Article II, but the president also has some other powers outlined elsewhere in the Constitution such as the ability to veto legislation. There are checks on many of these powers: the Senate must confirm appointments and treaties, and Congress is given the authority to declare war. But there are plenty of ambiguities here: if the president is the commander-in-chief, does he always need a congressional war declaration to use force? And does “faithful” execution of the laws really imply an ability to issue executive orders and take emergency actions?

These ambiguities represent the conception of the “fetus of monarchy” that some founders and the Anti-Federalists worried about. In the ensuing two centuries, Congress and the courts have allowed the fetus to grow by gradually conceding more and more authority to the president, broadening the powers enumerated in the Constitution and expanding the executive branch’s reach far beyond what was originally envisioned.

The Infancy of Monarchy: Thomas Jefferson Learns to Crawl (1803)

The Fetus of Monarchy may have been born during the events of 1803, when President Thomas Jefferson arranged for the “purchase” of the Louisiana Territory from France (National Constitution Center). Never mind the fact that France controlled only a small portion of the territory, which was mostly inhabited by Native Americans—essentially, the United States purchased the right to acquire the territory by treaty or conquest (Journal of American History).

(Spoiler alert: they mostly chose conquest.)

Jefferson himself questioned the constitutionality of the arrangement, stating “[The Constitution] has not given it power of holding foreign territory, and still less of incorporating it into the Union. An amendment of the Constitution seems necessary for this.”

Notably, he was totally fine with moving forward and just hoped the country would grant him the power after the fact: “In the meantime we must ratify and pay our money, as we have treated, for a thing beyond the Constitution, and rely on the nation to sanction an act done for its great good, without its previous authority.”

The Senate approved the treaty including the Louisiana Purchase despite constitutional concerns, effectively endorsing the president’s pushing of constitutional boundaries in foreign policy.

The Toddlerdom of Monarchy: Andrew Jackson’s First Word Was “No” (1829-1837)

The first words of Article I of the Constitution state “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” But later in the article, it gives the president the ability to essentially exercise legislative power through the veto. Andrew Jackson was the first president to wield this power effectively, marking the start of the stubborn toddler years.

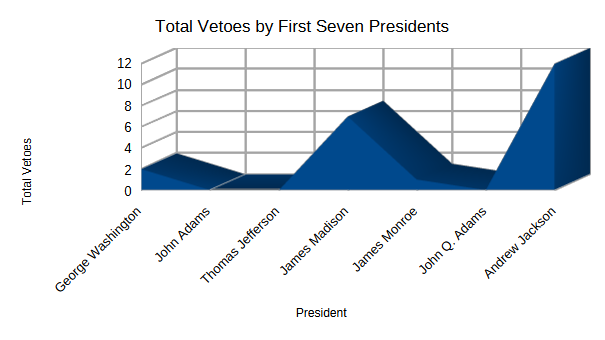

Before Jackson, vetoes were basically only used when a president considered something unconstitutional. Jackson began using them to dispose of legislation he simply disagreed with. In perhaps his most famous veto, he rejected legislation that would have rechartered the Second Bank of the United States, stating that it benefited the wealthy at the expense of commoners. While this was likely true, it set a precedent for the wider use of vetoes by future presidents. Congress did not act to override any vetoes until 1845, when it overrode an equally veto-happy president, John Tyler.

The Early Childhood of Monarchy: Honest Abe Tests His Limits (1860s)

Few presidents did more to expand executive power than old Penny-Face himself, Abraham Lincoln. When faced with an unprecedented crisis of southern states seceding and taking up arms against the United States, he tested the limits of presidential power by calling up 75,000 militia troops without a formal war declaration from Congress in order to suppress the rebellion. His swift action just months after assuming office prioritized preserving the union over strict adherence to the Constitution.

He later suspended the writ of habeas corpus, allowing for individuals to be arrested and detained without a trial. He justified this extraordinary move as essential to maintain public order during the war, and stated that it was preferable to letting the entire union collapse. The Constitution does allow for habeas corpus to be suspended during invasion or rebellion, but it does not specify which branch of government has that authority. The specific clause appears in Article I Section 9, potentially implying that it was meant to be a legislative power, but Lincoln assertively suspended it on his own authority.

Another power Lincoln wielded without clear constitutional permission was his issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. Through executive order he declared that all enslaved people in the territory calling itself the Confederate States of America would be “forever free.” Lincoln justified this move as a war measure under his authority as Commander-in-Chief: he argued that freeing slaves would undermine the Confederacy’s labor force, ultimately helping the Union war effort. At the end of the war the 13th Amendment was ratified, ending slavery in the south as well as in Union states not in “active rebellion” including New Jersey and Delaware.

Of course, the Emancipation Proclamation was a morally justified move that might have encountered resistance in Congress. However, that doesn’t change the fact that it was a unilateral action that set a precedent for future presidents to act similarly during crises.

Next Week: Executive Power During Reconstruction

Subscribe to How Important to catch future installments in this series about the expanding power of the presidency.